The Statement

Social media posts claim the Australian Constitution’s ban on “civil conscription” means that mandated or coerced vaccinations are illegal.

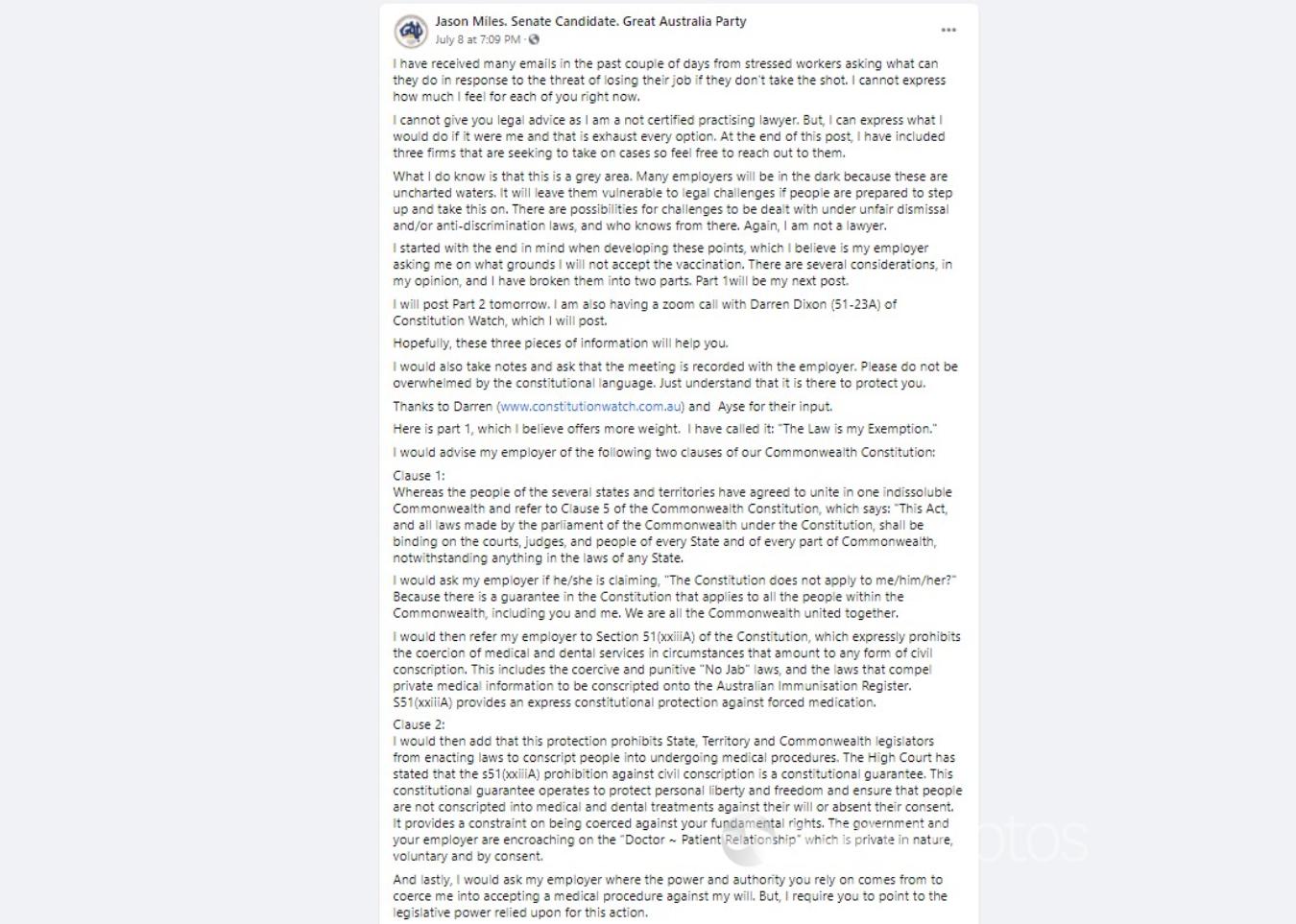

A July 8 Facebook post from Jason Miles, who is identified as being a candidate for minor political party the Great Australia Party, encourages workers to refer to the constitution if threatened with losing their jobs for refusing COVID-19 vaccinations.

The post claims the constitution “expressly prohibits the coercion of medical and dental services in circumstances that amount to any form of civil conscription”.

“This includes the coercive and punitive ‘No Jab’ laws, and the laws that compel private medical information to be conscripted onto the Australian Immunisation Register,” it states.

“S51(xxiiiA) provides an express constitutional protection against forced medication.”

Similar claims have been shared by several Australian Facebook accounts, including by the main page for the Great Australia Party and other accounts sharing the text of an article published in the Spectator Australia.

The Analysis

While the Australian Constitution may prevent the federal government from forcing medical practitioners to provide services – such as administering COVID-19 vaccines – it does not expressly bar the government from introducing vaccination requirements.

In June, the Australian government announced that COVID-19 vaccinations would be mandatory for all residential aged care workers by mid-September. Quarantine workers are also subject to vaccination mandates, however vaccinations remain voluntary for the general population.

However, the posts claim such measures are unconstitutional, pointing to section 51(xxiiiA) as proof.

This section states the parliament has the power to make laws for “with respect to the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorise any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances” (emphasis added).

Luke Beck, an associate professor of constitutional law at Monash University, told AAP FactCheck in an email that this section was added to the constitution in 1946 to “allow the Commonwealth to fund various social services schemes” such as Medicare, the pharmaceutical benefits scheme and payments available through Centrelink.

However, Dr Beck called the claim in the post “pseudo-legal nonsense”, saying the civil conscription limitation only prevents the federal government from forcing people to do work as doctors and dentists – it did not grant people individual “rights”.

The High Court dealt with the clause in 2009, when it ruled that requiring doctors to comply with professional standards in order to receive Medicare payments did not amount to civil conscription, he pointed out.

“There’s nothing in the constitution that would prevent a law making COVID vaccination mandatory. We have had mandatory vaccination rules for some professions for a long time in respect of other vaccines,” Dr Beck added.

Amelia Simpson, an associate professor at the Australian National University (ANU) who specialises in discrimination and equality principles in constitutional law, said the claim was “far-fetched” and “highly unlikely to be accepted by any court”.

She told AAP FactCheck in an email the prohibition on civil conscription was included to prevent the “forced enlistment of medical personnel to work for the government”.

“It was a response to the fears of the medical profession in Australia at the time (70 years ago) that their profession may be nationalised and their ability to work in private practice restricted,” Dr Simpson said.

“It has got nothing to do with coercive immunisation of citizens, then or now.”

The experts’ views are supported by an October 15 NSW Supreme Court decision following challenges to various workplace COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

In his decision to dismiss the cases, Justice Robert Beech-Jones, the state’s chief judge at common law, said the term civil conscription in the constitution was “directed to compulsive service in the provision of medical services” as opposed to the acquisition of services such as vaccinations by a patient (original emphasis).

Nevertheless, not all legal experts agree that the High Court would not extend the prohibition on “civil conscription” to also cover patients if it were asked to rule on the issue.

In an article published in The Spectator Australia, University of Queensland emeritus law professor Gabriël Moens and Augusto Zimmermann, a professor of law at Perth private college Sheridan Institute of Higher Education, argued that the constitutional clause meant “no law in Australia can impose limitations on the rights of citizens that directly or indirectly amount to a form of civil conscription”.

In an email to AAP FactCheck, Dr Zimmermann, who in January resigned from the Liberal Party over the implementation of strict COVID-19 restrictions, said the concept of vaccine mandates “sits uncomfortably” with the High Court’s jurisprudence.

“The constitutional prohibition of civil conscription can be construed as an right of individual patients to refuse vaccinations because their relationship with medical practitioners is contractual,” he said.

However, scientia professor George Williams, the deputy vice-chancellor and former dean of law at UNSW, told AAP FactCheck the clause could be used to prevent the Commonwealth – although not the states – from compelling doctors to take part in mass immunisation programs.

“On the other hand, it would not prevent the Commonwealth from requiring citizens to be vaccinated,” he said in an email.

Several experts also noted that the section of the constitution only relates to the Commonwealth’s power and does not cover responsibilities of the states.

Ron Levy, an associate professor with expertise in constitutional law at the ANU College of Law, told AAP FactCheck that even if a person somehow convinced a court to re-read the section to bar mandatory vaccination, that decision would not apply to any laws of the states.

Under the constitution, the Commonwealth is responsible for national health policies such as Medicare, whereas the states look after public hospitals and deliver preventative services such as immunisation programs (page 2).

Justice Beech-Jones also noted in his judgement that section 51 of the constitution only applied to the powers of the Commonwealth, not the states. He rejected the suggestion that this section of the constitution implied an individual right to refuse vaccination.

Similar claims about the constitution’s civil conscription clause barring forced or coerced vaccinations have previously been addressed on the Freeman Delusion website. AAP FactCheck has also debunked misleading claims that those refusing COVID-19 vaccines could be jailed under the Biosecurity Act.

The Verdict

Several legal experts say that the Australian Constitution’s “civil conscription” clause does not render mandatory COVID-19 vaccines illegal, although no such mandate has been introduced in the country for the general population.

They say this section only prevents the government from forcing doctors and dentists to undertake tasks against their will and it does not apply to the broader public. Their view is supported by a NSW Supreme Court judgement on COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

However, others have argued the same clause could be construed as extending the right of refusal to individual patients.

Missing Context – Content that may mislead without additional context.

AAP FactCheck is an accredited member of the International Fact-Checking Network. To keep up with our latest fact checks, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Updated October 7, 2021 15:30 AEDT: Comments from Gabriël Moens and Augusto Zimmermann added, verdict changed from “false” to “missing context” and headline altered to reflect the differing legal opinions.

Updated October 25, 2021 16:00 AEDT: References to NSW Supreme Court decision added.

All information, text and images included on the AAP Websites is for personal use only and may not be re-written, copied, re-sold or re-distributed, framed, linked, shared onto social media or otherwise used whether for compensation of any kind or not, unless you have the prior written permission of AAP. For more information, please refer to our standard terms and conditions.