A Facebook user says there’s no historical evidence of the traditional names of Indigenous groups and locations.

Instead, they claim the names are merely based on the “vibes of dreamtime” and “a few rock carvings”.

This is false. There are extensive records from early colonial times based on interactions between the British and Indigenous people.

Experts told AAP FactCheck these records are complemented by an extensive oral history.

The claim is made in a Facebook post (archived here) which describes aspects of Indigenous history as “a myth” and a “fraud”.

“WHERE in history can we see the actual names of the many indigenous tribes and location? NO evidence,” the post reads.

“Where do we find a language in authentic writing? No evidence.

“Then how can we rename geographical locations according to ‘just the vibes of the dreamtime’ with a few rock carvings.”

Several experts told AAP FactCheck the claim is ill-informed nonsense.

Stephen Gapps, an expert in early colonial history at the University of Newcastle, said from the First Fleet onwards the British interacted with the Indigenous population to ascertain names of people, groups and locations.

“One classic example is Governor Phillip and Bennelong. Bennelong was asked by Phillip and the First Fleet officers to describe who lived where around Sydney,” Dr Gapps said.

He notably told Phillip about the Aboriginal name of Parramatta, which the governor had at first called Rose Hill, but later renamed.

“Another early colonist that springs to mind was Charles Throsby, who on his travels in the bush to the southwest of Sydney toward Bathurst recorded the place name of where he was in his journal each night,” Dr Gapps said.

“Many of those names are places we know today, Burragorang, Warragamba, as well as Gandangarra people.”

He cited Thomas Mitchell and Hamilton Hume as others who had contributed to recording traditional names.

Harold Koch, an expert in Aboriginal languages at the Australian National University (ANU), provides examples of early colonial manuscripts detailing traditional names in his 2009 book Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and re-naming the Australian landscape.

In particular, he features the work of William Dawes, who arrived on the First Fleet’s flagship HMS Sirius, on pages 15, 16 and 17 of the book.

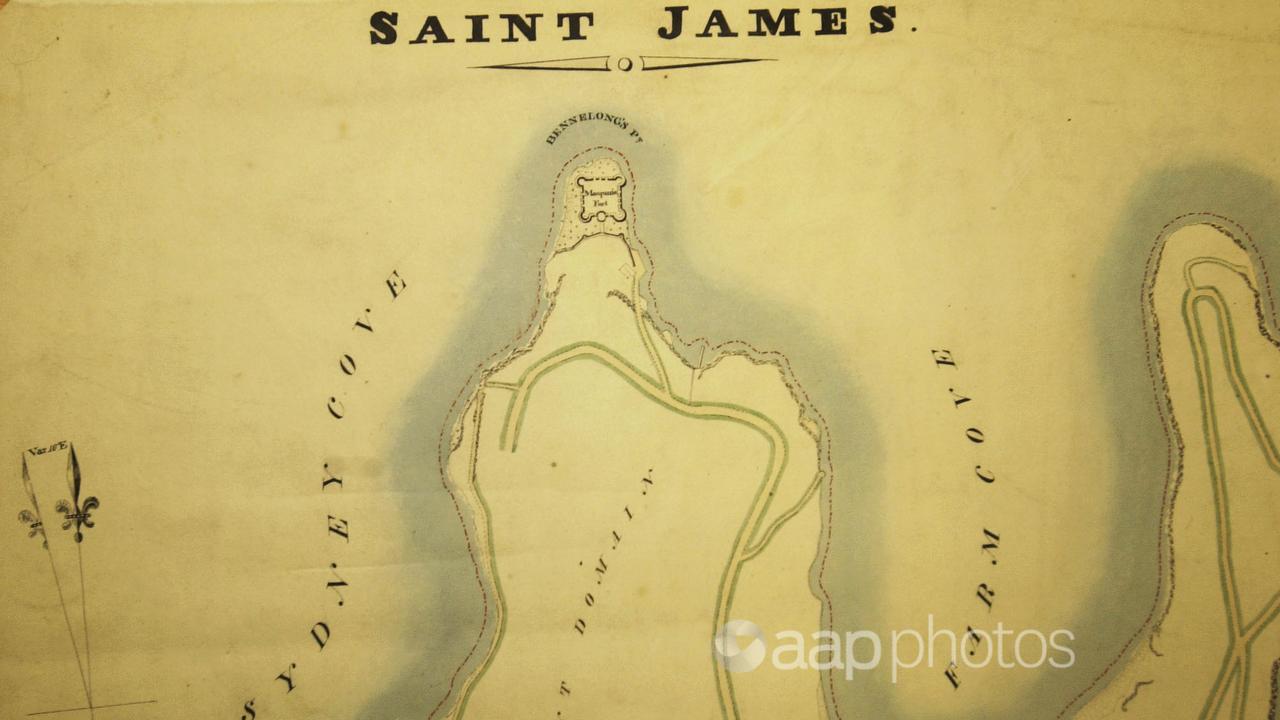

Dr Koch notes traditional names were mostly recorded in wordlists in the colony’s early years, but there are examples of maps such as this from 1796 courtesy of Charles Grimes and this from the same year by Governor John Hunter.

Heidi Norman, an expert in Aboriginal political history at the University of Technology Sydney, said records were made from the early weeks of contact in 1788.

Professor Norman said it was not just early maps and documents that recorded the information, but also objects such as gorgets given to Indigenous people to “reinforce the leadership status the colonists observed”.

As well as featuring traditional names, the plates recognised the connection of groups to certain areas.

Richard Broome, an emeritus professor at La Trobe University, described the claim as nonsense and pointed to the maps produced by anthropologist Norman Tindale.

Dr Jane Simpson, an expert in Indigenous language at ANU, said the British not only recorded the names of places but also words indicating land ownership.

Experts told AAP FactCheck the post also fails to take into account the rich tradition or oral history among Indigenous communities.

Dr Imogen Wegman, an expert in early colonial history at the University of Tasmania, said the post’s main issue was the misguided belief that a culture needs a written language to have a cultural memory.

Prof Norman said aside from colonial records, the knowledge among Aboriginal people “was continued and was renewed” in the early years of the colony.

“Today, and perhaps ironically, it is the written records and archives of the colonisers and settlers, alongside and illuminated by Traditional Knowledge, that is drawn upon by experts to prepare support material for Native Title claims,” Prof Norman said.

The Verdict

The claim there is no historical evidence of the names and locations of Indigenous groups is false.

The British began recording the traditional names of locations, groups and their associations with locations from the early weeks of contact in 1788.

The results are recorded in various historical documents. These are complemented by the tradition of oral history among Indigenous communities.

False – The claim is inaccurate.

AAP FactCheck is an accredited member of the International Fact-Checking Network. To keep up with our latest fact checks, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

All information, text and images included on the AAP Websites is for personal use only and may not be re-written, copied, re-sold or re-distributed, framed, linked, shared onto social media or otherwise used whether for compensation of any kind or not, unless you have the prior written permission of AAP. For more information, please refer to our standard terms and conditions.