When David Levitt opted to undergo voluntary assisted dying, the one most distressed was the family dog.

For the rest of his loved ones, the end of Dr Levitt’s life was peaceful and gentle.

His wife Pauline McGrath hopes other terminally ill Australians can die the way they want.

“He just wanted to die being held by the people who loved him most in the world,” she said.

“We laid him in bed, we surrounded him, and we talked to him about how important he was.

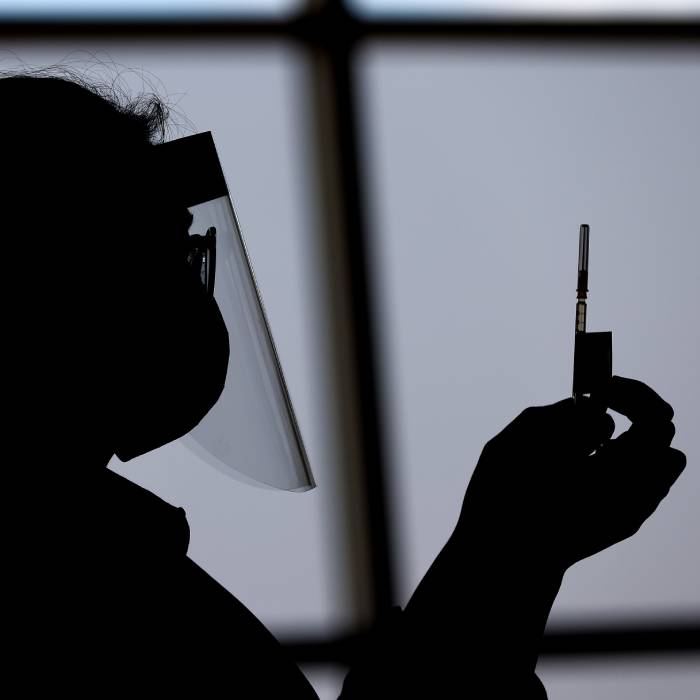

“He drank the substance, and within two minutes, David gently went to sleep.”

In 2017, Victoria became the first state to legalise voluntary assisted dying, intended for those with a terminal illness suffering immense pain and wanting control over the circumstances of their death.

Other states have followed suit, with voluntary assisted dying soon to be legal in every Australian jurisdiction except the Northern Territory, and demand is projected to grow.

Since 2017, some 2460 people have opted to end their lives with the service, a landmark report by charity Go Gentle Australia found.

Go Gentle Australia chief executive Linda Swan said the evidence painted a “reassuring picture of systems fulfilling their aim”, with health professionals providing “kind and meticulous” support.

“None of the dire predictions from opponents have come to pass and systems are working safely and with great compassion,” she said.

But barriers stand in the way of access for many Australians and Dr Swan said it was not clear if the right balance between safeguards and accessibility had been achieved.

For example, provisions in the Commonwealth Criminal Code make it illegal to encourage others to take their own lives over digital communication platforms.

Voluntary assisted dying applicants must attend all appointments in person, which is particularly burdensome for those living in regional or remote areas.

Living in west Brisbane meant Dr Levitt was zoned into faith-based care institutions, where discussions over voluntary assisted dying were not supported.

Fearing the worst, the couple withdrew completely from palliative care.

Health bodies including the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia and the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation are calling for reform so people can use phone, email and telehealth as part of the voluntary assisted dying process.

“I saw (the prime minister) on TV say that voluntary assisted dying was too important to use telehealth for,” Ms McGrath said.

“What I would actually say is voluntary assisted dying is too important not to use telehealth for.”

“Gag clauses” in South Australia and Victoria also prevent health professionals from raising the option with patients, meaning many did not know voluntary assisted dying was available.

“No other health care requires patients to know their treatment options before consulting a doctor,” Dr Swan said.

More health professionals need to be encouraged to complete voluntary assisted dying training, the report says, recommending they be fairly compensated for the education.

The government was working with health professionals on the issue, Health Minister Mark Butler said.

He acknowledged a lack of access to voluntary assisted dying could also have consequences for those who are left behind.

“There is still much to do to get past longstanding challenges to ensure these inevitable, but powerful, poignant moments can happen in a way that is shaped by choice and control of the family,” he said.

Lifeline 13 11 14

beyondblue 1300 22 4636