Content creator and science educator Michelle Wong lives by the three-second rule.

She uses her chemistry PhD knowledge to debunk misinformation about cosmetics while knowing her 500,000 followers will give each of her videos just three seconds before they decide to keep watching or scroll on.

The problem is, science takes more than three seconds to explain – but there are no such limits on misinformation.

“With science, it’s really hard to make it catchy, with misinformation, you can do whatever you like,” Dr Wong tells AAP.

“You can make it as catchy as you like because you aren’t bound by truth.”

Dr Wong has made a career from tackling falsehoods, particularly around sunscreen, and says it’s important people understand the science behind why it’s safe because the problem translates into the food and health space.

“The same sort of logic that is in cosmetic science misinformation such as sunscreen misinformation also carries on to more serious issues, things like vaccines, disinformation around health and cancer cures,” she says.

The Combating Misinformation Bill before federal parliament seeks to address the spread of misinformation and disinformation, aiming to minimise their impact and force social media giants to take accountability for what’s on their platforms.

It’s far from guaranteed to pass, with the coalition opposing it over concerns it could impact free speech, and cross benchers including the Greens yet to reveal their position.

It’s drawn mixed reaction. The Australian Human Rights Commission insists the bill shouldn’t be passed in its current form and faith groups like the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference worry that their beliefs could be classified as misinformation.

The Australian Electoral Commission says there’s value in promoting transparency and accountability, while the Press Council, Fighting Harmful Online Communication and the Executive Council of Australian Jewry are among those pushing for changes.

“We’re in a bit of a difficult situation, some would argue that the bill is really not perfect, it could probably barely be considered good, but it does seem that something needs to be done right now,” according to Human Rights Law Centre Senior Lawyer David Mejia-Canales.

The bill would replace the voluntary industry code of conduct, which X and Snapchat don’t abide by, with a self-regulation scheme.

The focus wouldn’t be on individual posts or accounts but on systemic issues, forcing tech companies to hand over data on misinformation to the Australian Communications and Media Authority.

There are no criminal penalties and down the track the regulator could decide if there should be an enforceable code of conduct or other standards.

The proposed legislation has also drawn criticism from billionaire X owner Elon Musk, who has labelled the government “fascists”, while other tech giants are working on their responses.

Mr Mejia-Canales says while it’s not perfect, his organisation is pushing for the bill because “doing nothing right now is not an option”, pointing to a spate of instances where misinformation has spilled over into real world harm.

Earlier this year, a man was incorrectly identified online as the perpetrator of the Bondi stabbing attack, which was then amplified by traditional media.

Riots in the UK were sparked by false claims an asylum seeker had killed girls at a Taylor Swift dance event.

Mr Mejia-Canales had hoped Australia would bypass self-regulation and follow the European Union’s “gold standard” Digital Services Act he says unleashed a trove of data from big tech companies but he’s relying on the Australian law to be updated in the future.

“Self-regulation, on its face, just doesn’t work. It hasn’t worked for banks, it certainly hasn’t worked for supermarkets,” he says.

“Platforms actually profit from mis- and disinformation on their service, so they don’t have a commercial imperative to really do something about the problem, unless they’re forced to.”

That’s in contrast to the Victorian Bar, which describes the definition of misinformation in the legislation as “unworkable” and serious harm as “over-broad”, bringing about “chilling self-censorship”.

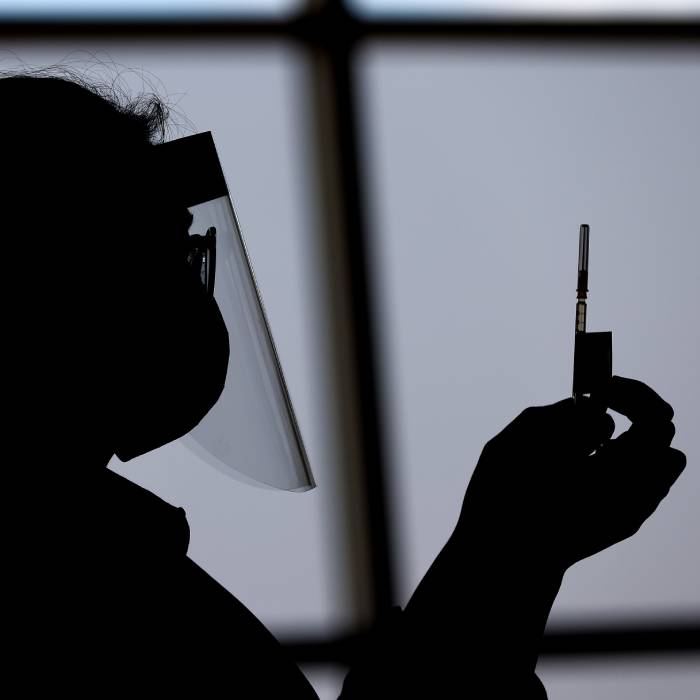

Former deputy chief medical officer and face of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout Professor Nick Coatsworth is worried it presents more problems than solutions and can’t be effectively implemented.

“In the attempt to limit ‘verifiably false’ information on social media, it is likely legitimate debate over public health priorities and concerns about the efficacy and necessity of public health measures would be stifled,” he says.

Individuals wouldn’t be held accountable under the bill and it doesn’t apply to all questionable Whatsapp messages or Facebook rants, only to content deemed seriously harmful and verifiably false or deceptive.

It also has to fall within distinct categories of elections, public health, inflicting physical injury, vilification or causing imminent harm to the economy, infrastructure or emergency services.

Australian media companies are exempt as they are already regulated under Australian law.

Monash University’s head of politics Zareh Ghazarian says it would likely play well with many voters at the next federal election due to be held by May.

“In terms of the politics of this bill, it’s very much a good news story for the government because this is all framed about introducing greater accountability, greater safeguards, these are positive messages,” he says.

Australia does not have federal truth in advertising laws and Dr Ghazarian suggests it may become a by-product of the misinformation crackdown.

“(The bill) presumably also has potential to impact political communication as well without the government necessarily introducing an explicit political advertising law,” he says.

Its future remains up in the air, negotiations with crossbenchers continue and a committee report on it is due back on November 25, which would allow the government one final sitting week to try and get it passed this year.

The opposition won’t support it even with a major overhaul.

Shadow communications spokesman David Coleman claims the bill would cause “immense damage” to Australia’s democracy.

“It will mean contested political issues become subject to censorship,” he says.

He has hit out at a lack of transparency and accountability, with public submissions on the bill open for seven days and some parties unable to give feedback on the complex legislation.

Communications minister Michelle Rowland also dismisses doing nothing as an option.

“Serious misinformation and disinformation pose a serious threat to the safety and wellbeing of Australians, as well as to our democracy, society and economy,” she warns.

“The coalition’s plan to oppose the misinformation bill shows they’re more interested in playing politics than protecting the health and safety of Australians.”

Dr Wong is in favour of a “top-down effort” to quash misinformation but isn’t sure the current push is the best way forward.

She says Australia is in a better situation than the US where science misinformation has become politicised but is worried moderate Australian opinions could be pushed out, with more extreme opinions from overseas coming in.

“Science is relatively objective but there’s still a lot of examples where the understanding is shifting; the reason it shifts is because of very outspoken scientists,” she says.

“It could potentially be used to punish people who are going against the status quo and the chilling effect could very well hold back scientific progress.”