In the darkness ahead, crewman Graham Kemp saw the Tasman Bridge suddenly looming up ahead on Hobart’s River Derwent, as the captain of the Lake Illawarra tried desperately to change the bulk carrier’s course.

It was 9.27pm on January 5, 1975, and less than two weeks after Cyclone Tracy had decimated Darwin, another disaster was about to stun Australia.

The ship was off course as it neared the bridge, partly due to the strong tidal current but also because of inattention by the ship’s master, Captain Boleslaw Pelc.

“Kemp, who was on the bow, saw the bridge and thought ‘shit, I’m going (to go) backwards’,” says historian Tom Lewis, author of the book By Derwent Divided, which has been republished to mark the 50th anniversary of the tragedy.

But Mr Kemp was told over the ship’s PA, ‘turn around, go forward, drop the anchor’.

“He turned and obeyed, he went forward, he dropped out (the anchor) and it went down immediately,” Dr Lewis told AAP.

“But of course, it was too late, and the ship hit the bridge and came down on top of him.”

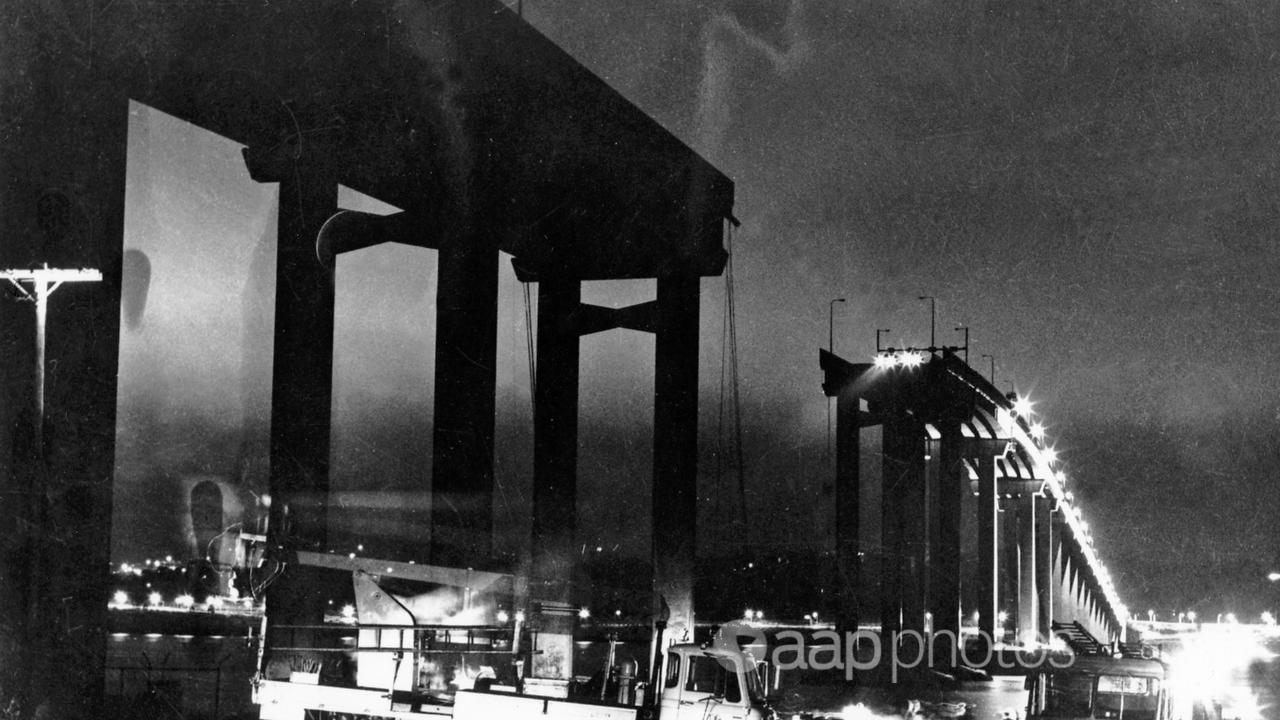

The vessel crashed into the pile capping of pier 18 and then pier 19 of the 1025m bridge, and both collapsed, bringing three spans crashing onto the hull of the vessel, which sank in minutes.

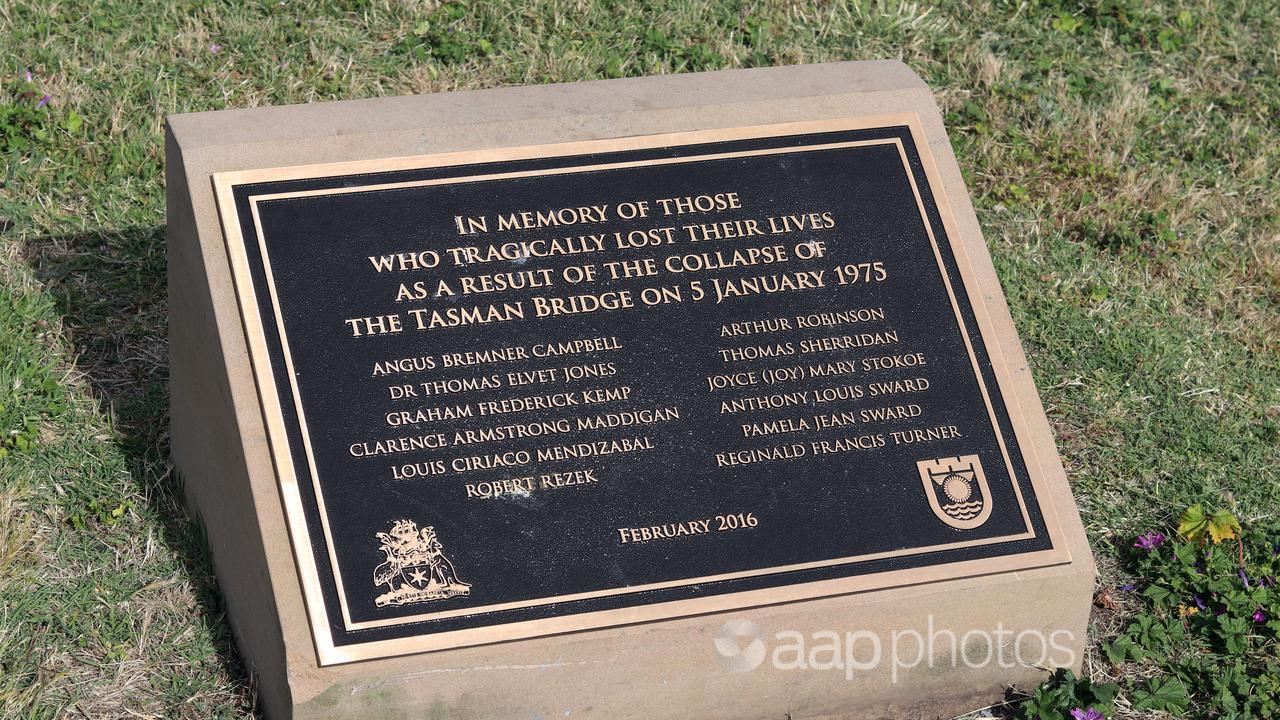

The collision had fatal consequences for seven crew including Kemp – who was awarded a posthumous bravery award – and five people in four cars that plunged from the bridge.

It also had a far-reaching impact on the residents on the eastern shores of the city, which suffered nearly three years of dislocation that cost tens of millions of dollars.

Frank Manley, now aged 94, remembers driving towards the bridge when he saw its lights go out, but he had no idea that three unsupported sections, spanning 127 metres, had just tumbled into the river.

He was returning from a barbecue with his wife, daughter and brother-in-law in their new HQ Monaro coupe.

“And then the wife and I spotted that the white line down the road was missing,” Mr Manley said.

“And the wife said, ‘the bridge is gone, the bridge is gone!'”

He “put the anchors on fairly hard”, he said.

“Next thing, the car hung over the edge a fair way. And then the wife said, ‘put her in reverse’.

“I said: ‘Bugger reverse, get out as quick as you can’, because there could be another car coming down the bridge’.

“Another inch, and we would have been gone.”

They quickly exited their car and noticed another family of four in an FB Holden station wagon stopped nearby.

Mr Manley’s brother-in-law John pleaded with the family to get out and minutes after they did, another vehicle crashed into their car, pushing it to the edge.

Iconic photographs show both cars precariously perched, their headlights blazing into the darkness.

Mr Manley’s daughter tried to flag down a tourist coach, hitting it to get the driver’s attention.

“The bus driver wound the wind down and said: ‘Get out of it, you cranky so-and-so’ and he kept driving,” he said.

“When he got another few metres up the bridge, he realised what had happened.”

Police later told Mr Manley they might have to push his car into the river “and that upset me a bit”.

But it was safely towed away and five decades later, it remains his pride and joy.

The Monaro and the FB station wagon are together again for the first time since 1975, at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s On The Edge exhibition until January 12.

In the minutes after the collision, civilians in small vessels risked their lives amid falling concrete and live wires to rescue Lake Illawarra’s crew.

Dr Lewis said the damage to the 11-year-old bridge created chaos for people living on the city’s heavily populated eastern shore, and attention immediately turned to how to restore a transport link.

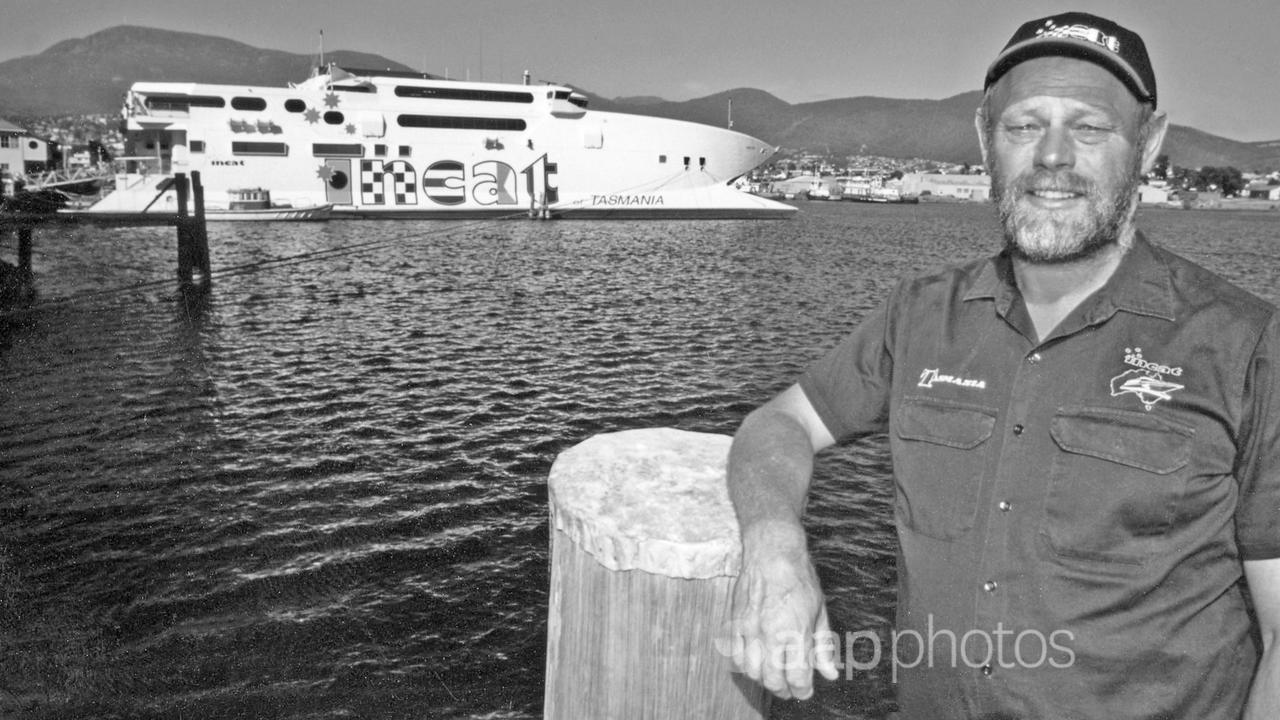

Bob Clifford ran the Sullivans Cove Ferry Company, which operated two boats across the Derwent, both used in the rescue operation.

“He’s a remarkable fellow,” Dr Lewis said.

“He had two of those little aluminium ferries instantly going backwards and forwards.”

“But he did it for free before he finally said to the government, ‘look, I need to pay my way here’.”

Income from the ferries allowed Mr Clifford to commission Hobart-based Marine Constructions to build more vessels, and he took over the company.

Eventually, he had five boats operating on the harbour and transported more than nine million people in the two years after the collapse.

Mr Clifford went on to found Incat, a catamaran ferry builder which is undergoing a major expansion and is building the world’s largest electric ferry.

An inquiry found that Captain Pelc had not handled the Lake Illawarra in a proper manner, and his certificate was suspended for six months.

“You look at it and say, well, 12 people died, surely there should be more of a penalty,” Dr Lewis said.

“But I suppose there was more of a penalty – he never went to sea again and basically lost his job. He just went into retirement and later died.”

The ship herself could not be moved without the risk of causing further damage to the bridge.

“Every time I drive across the Tasman bridge, I think, ‘Lake Illawarra’s down there’,” Dr Lewis said.

“That’s macabre, really. It’s got two bodies on it.”

The bridge reopened on October 8, 1977, and Mr Manley agreed that he was a bit anxious the first time he drove his Monaro on it again.

“You wear into it, like a new pair of boots,” he said.

The museum will host a private commemoration on January 5 for families of those who lost their lives, who were on the bridge or the Lake Illawarra at the time of impact, or who were part of the project to rebuild the bridge.

“There’s not too many of us left,” Mr Manley said.

The Tasman Bridge will be closed for three minutes from 9.27pm on January 5 and its feature lighting will be dimmed to dark blue between piers 17 and 19 from 9.27pm to 9.57pm.