It’s hard to think vilification could inspire something positive but it just made eight-year-old Penny Wong determined to shine.

As a immigrant child growing up Adelaide, she was the first Asian Australian pupil to enrol at Coromandel Valley Public School and the first Asian some of the other kids had ever seen.

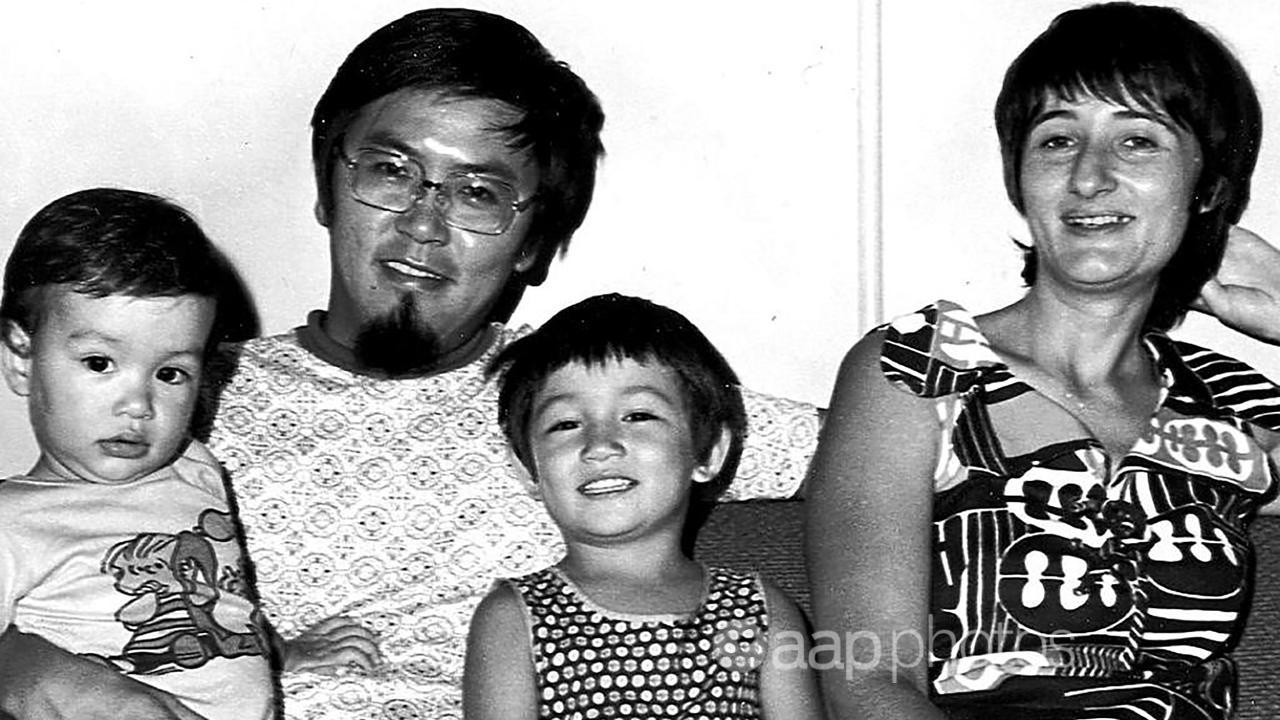

Born Penelope Ying-Yen Wong to architect dad Francis and English-Australian mum Jane in Kota Kinabalu, eastern Malaysia in 1968, she arrived in Australia in 1977.

“Unfortunately, by chance, one of our neighbours had a problem with Asian immigration,” she recalls.

“It was a very difficult time.”

There was bullying and abuse. The driveway to the family home was graffitied.

But the way she dealt with it was just to silently say, “I’m going to be really good at everything.”

“This is eight-year-old Penny talking to herself,” the now foreign minister and leader of the government in the Senate recounted at the seventh annual Asian-Australian Leadership Awards in Sydney on Thursday evening.

“But it did teach me to focus on what you want to do. It brought a determination.”

Senator Wong, 56, was honoured at the ceremony for her lifetime of achievement.

Refusing to allow the prejudice of others to derail them was a lesson she now taught her own children, she said.

“We are not ever defined by someone else’s hate or anger.”

Asked how far multiculturalism had come since she entered politics in 2001, Senator Wong described diversity as a national asset “to be proud of”.

Yet there is still a way to go.

“We are a lot further along in some ways but still behind where I would want us to be in leadership in the parliament and in big Australian companies,” she said

While women represent 51 per cent of the population, it is only in the current federal parliament that anything like gender parity has been achieved. They fill 118 seats across both houses, or 44.5 per cent.

Migrant MPs are scarce by comparison. Of 230 in total, 59 identify as having non-English speaking ancestry.

Senator Wong and little brother Toby grew up speaking Bahasa Malaysia and specifically the dialect known as Sabahan; Chinese, including their vernacular dialects of Cantonese and Hakka; and English, which was the home language they spoke with their mixed-race parents.

The challenge for her was identifying her own path.

She was educated at Scotch College and then the University of Adelaide, graduating with an arts law degree. Before entering politics, she worked as a lawyer and political advisor.

After winning a South Australian Senate seat in 2001, the first Asian-born person to do so, she was appointed climate change minister in 2008, becoming the first openly LGBTQI member of cabinet.

“We all have different ways of leading,” she said.

“Knowing who you are and what you want to do in the world, isn’t that where everything starts?”

The Asian-Australian Leadership Awards are judged across 11 categories.

This year’s overall winner was Charlotte Young, 22, co-founder of the Australian National University Auslan Club and an inclusivity consultant to the Australian government, UNICEF and the US Embassy.

Others included University of Queensland research director Amirali Popat and multi-instrumentalist and composer, Filippina-Australian Victoria Falconer.

A survey of previous winners found 93 per cent believed their Asian-Australian heritage has been a barrier to their success.

“The awards seek to reshape debate and confront Australia’s ‘bamboo ceiling’,” Asialink chief executive Martine Letts said.

“It’s very difficult to break through that ceiling if your identity and cultural heritage hold you back.”