Etched into his bedroom walls is the history of some of Australia’s notorious killers. Once an adult prison, the three-by-two metre concrete cage now holds the trembling teen captive.

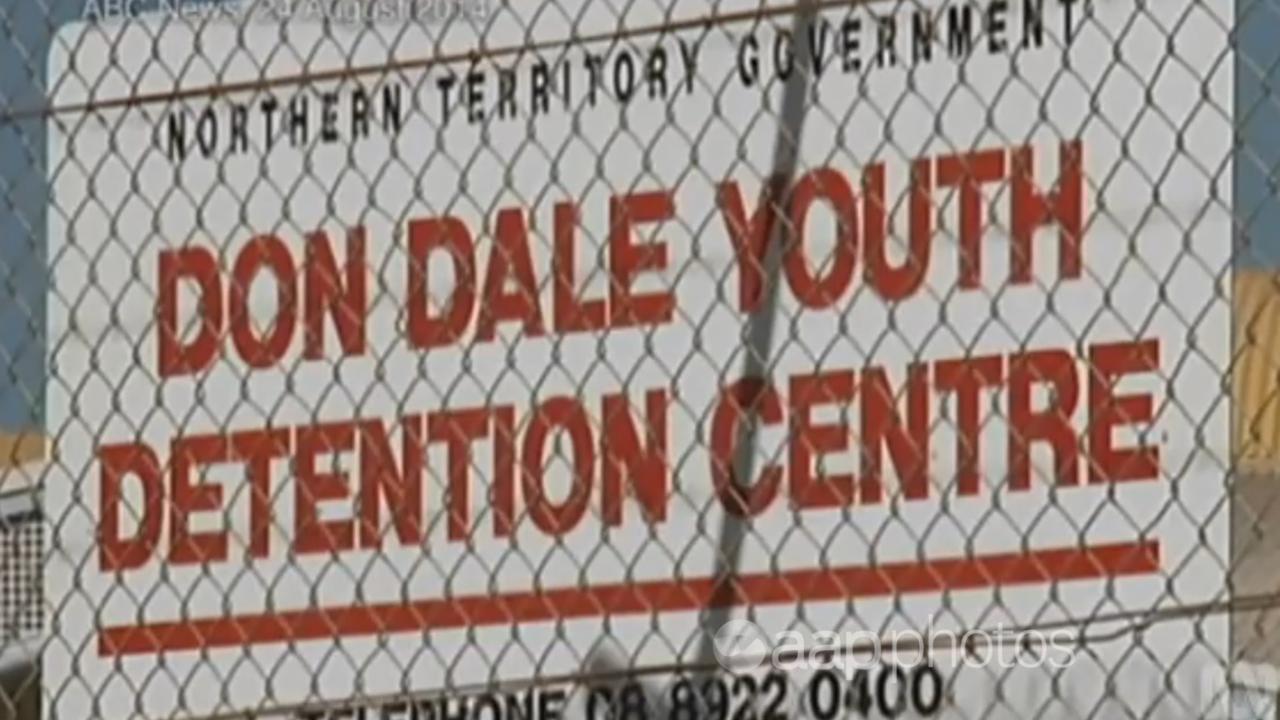

After almost two years of near solitary confinement in Don Dale Youth Detention Centre’s notorious H Block, the 16-year-old is wrestling with hope.

“He’s terrified all the time. He’s been self-harming … just to go to hospital and to get out of that cell,” his distressed father tells AAP.

“He tells me he wants to come out so bad but then sometimes when he does, he just wants to go back. It’s (screwed) with his head.”

Through gritted teeth and sobbing, his father says his son hurting himself is both a plea for help and a protest at the conditions.

“To tell you the truth, the dog pound is better conditions than where I seen my son,” he says.

“As I walked in, the smell of raw sewerage was just overwhelming. I was nearly vomiting.

“This place would break the most hardened criminal. He’s just a little boy. He has done the wrong thing but how can this be allowed?”

First incarcerated at 11, the boy, who can’t be named for legal reasons, has spent most of his youth inside the facility in Darwin’s north.

Currently serving a four-year sentence for driving unlicensed and four counts of assault, court documents reveal the teen often becomes dysregulated – lashing out at others and property.

A multidisciplinary assessment provided to the court highlighted that, in addition to multiple neurodevelopmental disorders, he grew up in a home with intergenerational violence and addiction.

The impact of those difficult childhood experiences are said to be “causal risk factors” for his developmental maturity and antisocial behaviours. He disengaged from school at a young age.

The documents show he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, which leads to nightmares and frequently self-harming as a result of being in youth detention.

Family and support agencies have raised concerns about his ongoing isolation, the conditions he is held in and his rehabilitation.

A spokesperson from NT Territory Families says young people often have complex behavioural issues and separation is used to ensure the safety of others.

“We recognise long-term support is needed to help these young people, which is why we have a range of comprehensive behavioural supports.”

The Office of the Children’s Commission in the Northern Territory has condemned the ongoing use of isolation.

“International standards for how children are to be treated in detention require that isolation practices, by whatever name, are only used in exceptional and clearly defined circumstances, for the shortest duration and prohibited as a form of punishment,” NT Children’s Commissioner Shahleena Musk says.

“Separating children alone in their cells, especially for prolonged periods, can have a significant impact on their physical and mental health, and are counterproductive to improving behaviours or safety.”

Six years after a royal commission recommended the closure of Don Dale, up to 50 children remain there, despite a new $70 million facility sitting empty 18km away.

Productivity Commission data shows following the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory, daily numbers dropped to as low as 20 but have steadily climbed in the past six years.

This week, the territory government plans to repeal the age of criminal responsibility from 12 to 10, despite warnings from local and international experts.

Chief Minister Lia Finocchiaro believes the crime crisis in the territory needs a “crisis” response, which she plans to enforce with greater police powers, including the reintroduction of spit hoods on children, which was banned under the previous Labor government.

“Youth offenders under 12 are falling through the cracks in the territory. This is why we will lower the age of criminal responsibility from 12 to 10,” Ms Finocchiaro said.

“Ignoring young people who commit crimes is not the answer to turning their life around.”

The news comes as other states and territories consider raising the age of criminal responsibility.

Some of the answers to the child-crime conundrum could be found 14,000km away.

In September, Scotland announced it had no one under the age of 18 incarcerated after almost two decades of work addressing youth crime.

Glasgow was once considered the most dangerous city in Europe, with a knife crime occurring every six hours.

The woman behind the feat is forensic psychologist and Community Justice Scotland chief executive Karyn McCluskey.

“Our (criminal age of responsibility) was 10 as well,” she said.

“We raised it to 12, everybody said it was going to be terrible and of course, nothing happened.

“And we’ll probably raise it again – the evidence tells you that you have to raise it so much.”

Despite raising the age, not only have incarceration rates dropped but homicides and knife crime statistics are at the lowest levels since records began.

Ms McCluskey says the key to success is 20 years of consistently approaching crime as a public health crisis and redeploying existing funding in the justice system.

“There was quite a lot of money in the system, and there still is, although people don’t like to admit that,” she says.

“We were just focusing it on the wrong places and we were not working together to try and influence the same outcomes.”

Simple changes, such as a no-expulsion policy for schools, and supporting teachers to keep young people safe and engaged at school were heralded as “heroes” of the program.

“We knew that every kid they kept at school was one less kid we got in jail,” Ms McCluskey says.

“I do always say prison and the justice system is like an infection – once you get in it, it becomes lifelong and life-limiting – so the best thing to do is try not to get in it in the first place.”

Reflecting on the territory government’s plan, Ms McCluskey says it’s the “wrong decision”.

Governments are happy to build new prisons because it appeals to people who think locking everyone up works, she says.

“But I keep saying to people, if you’re building criminal justice capacity for 15 years in the future, that’s like saying to a five-year-old child … that is their future.

“It seems less than aspirational.”

Lifeline 13 11 14

beyondblue 1300 22 4636

13YARN 13 92 76