The Statement

A Facebook post has been promoting the use of a large intravenous dose of vitamin C to "stop COVID-19".

The post, from September 20, includes an image of a sign on the back of a truck stating: "Stop COVID-19 with vitamin C 20g to 30g intravenous, drip (sic)".

At the time of publication, the post had been shared more than 820 times, attracting more than 3500 reactions and 180 comments. The same image was later shared on the NZ Journal of Natural Medicine Facebook page, among other places.

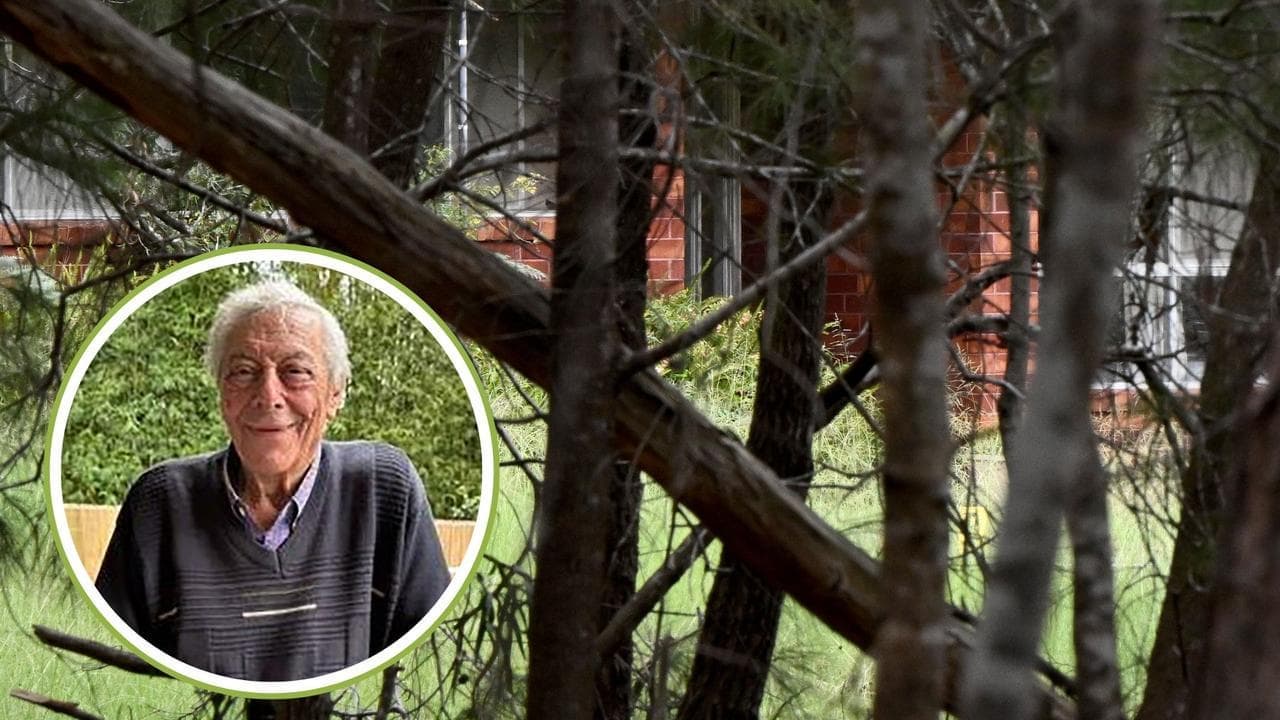

The post was on the Facebook page for Andrew W Saul, whose online bio states he is a New York-based author with a doctorate in "behavioral biology".

He has written a number of books advocating for the use of multivitamins to treat conditions such as alcoholism, depression and "women's health problems", and refers to himself as "the megavitamin man".

The caption accompanying the post's image reads, "The sign is not my own, but I think it is a nice touch."

The Analysis

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, vitamin C products have been reportedly "flying off the shelves" as people seek to boost their immune systems during the pandemic.

According to the US National Institute of Health (NIH), vitamin C plays an important role in the function of the immune system. It recommends adults consume between 75 and 90 milligrams a day (table 1), roughly the amount of the vitamin found in three-quarters of a cup of orange juice (table 2).

But can an intravenous dose of vitamin C at hundreds of times this level - 20 to 30 grams - prevent COVID-19, as the post claims?

Research on the use of high doses of intravenous (IV) vitamin C for a range of conditions suggest it may have benefits in some cases. But reviews into the use of vitamin C to treat COVID-19 have been mixed, and there is no evidence to suggest that high doses of IV vitamin C could prevent people from contracting the coronavirus altogether.

A review of treatments for COVID-19 by Harvard Medical School pointed to earlier studies showing high doses of IV vitamin C may help treat sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which were were "the most common conditions leading to intensive care unit admission, ventilator support, or death among those with severe COVID-19 infections".

But it added "there is no evidence that taking vitamin C will help prevent infection" and high doses of vitamin C could cause nausea, cramps and an increased risk of kidney stones.

A study published in PharmaNutrition in April looked at the potential for using high doses of IV vitamin C for treating ARDS in COVID-19 patients.

It said vitamin C had shown benefits in reducing symptoms and mortality in some conditions (page 2) and "additional studies detailing the use of IV Vit-C for the treatment of severe Covid-19 infected pneumonia are definitely warranted" (page 6).

A non-peer-reviewed overview of the effectiveness of treating COVID-19 with vitamin C by researchers from the University Hospital of Zurich was published in April. It found there was no scientific evidence that either oral or intravenous vitamin C was beneficial in treating the virus.

Another review, published in the Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance in October, found high doses of vitamin C may "favourably impact patients with viral pneumonia and ARDS in severe SAR-CoV-2 infected patients".

Patients were recruited for a clinical trial in Wuhan, China, into the use of vitamin C for COVID-19 in February, however it didn't reach its planned sample size as the city's outbreak was brought under control and the number of qualifying patients available decreased.

Researchers released a non-peer-reviewed preprint study in August after 27 critically ill COVID-19 patients were given 24g of IV vitamin C daily for a week.

The study found the treatment "may provide a protective clinical effect without any adverse events in critically ill patients with COVID-19".

At least three other trials are underway - in Canada, the US and Italy - but their results are yet to be published.

Meanwhile, in its series of COVID-19 "mythbusters", the World Health Organisation notes vitamin C's critical role in the immune system but adds there is no current guidance on its use as a treatment for the virus.

The NIH's COVID-19 treatment guidelines say the use of high-dose vitamin C in COVID-19 patients is being studied, but there is insufficient evidence on its effectiveness. They note there is "no compelling reason" for the use of vitamin C in non-critically ill patients as they were less likely to be experiencing severe inflammation.

In Australia, the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care released a position statement in May on the use of high-dose IV vitamin C for COVID-19.

It said the vitamin could support defences against infection but added there was "no robust scientific evidence to support the usage of high-dose intravenous ascorbic acid (vitamin C) in the management of severe cases of COVID-19".

In March, Australia's Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) found there was "no evidence to support intravenous high-dose vitamin C in the management of COVID-19" and further research was needed.

A spokesperson for the TGA told AAP FactCheck via email that "there remains insufficient evidence to support the use of intravenous vitamin C in the management of COVID-19".

Magreet Vissers, a professor at the University of Otago's Centre for Free Radical Research who specialises in the use of vitamin C in treating disease, said advocating a 30g intravenous dose to prevent COVID-19 was "a stupid thing to say".

"It's one step above injecting yourself with bleach," Prof Vissers said. "It's probably not harmful but it's not going to keep you safe."

She said a dose of about six to 10 grams of vitamin C each day could be beneficial for people who were critically ill as the body could become severely depleted of the vitamin, reducing the function of the immune system and other essential bodily processes.

But Prof Vissers said people were generally able to maintain a saturation level of vitamin C through a healthy diet and taking a high dose of vitamin C intravenously would not help the body fight off COVID-19.

University of Otago associate professor Anitra Carr also studies the role of vitamin C in human health, including in pneumonia and sepsis. She told AAP FactCheck via email "there is as yet no published data to indicate that high-dose IV vitamin C will prevent COVID-19".

She said the Wuhan study indicated vitamin C infusions could decrease mortality in the most severely ill COVID-19 patients, but noted the study had a small sample size and it was undergoing peer review.

Professor Mary-Louise McLaws, an epidemiologist and researcher at the University of New South Wales, told AAP FactCheck via email that there was no evidence that taking large doses of vitamin C intravenously could stop the spread of COVID-19.

Prof McLaws said there was evidence using IV vitamin C could help people with pneumonia caused by COVID-19, but it was "too early to determine the impact" until more research was conducted.

Similar claims from Andrew Saul have been fact-checked as false here and here, while others relating to the use of vitamin C to treat COVID-19 have been debunked here and here.

The Verdict

AAP FactCheck found the central claim in the post to be false. Administering 20 to 30g of vitamin C intravenously cannot "stop COVID-19", as suggested in the image.

Some evidence suggests high doses of intravenous vitamin C may help critically ill patients with COVID-19, but further research is required to determine the efficacy of the treatment.

There is currently no evidence that taking high doses of vitamin C intravenously prevents people from contracting COVID-19. Experts say a healthy diet should be enough to ensure adequate levels of the vitamin to support a healthy immune system.

False – Content that has no basis in fact.

* AAP FactCheck is accredited by the Poynter Institute's International Fact-Checking Network, which promotes best practice through a stringent and transparent Code of Principles. https://aap.com.au/