AAP FactCheck Investigation: Have soldiers been given the same powers of a police constable?

The Statement

"So now, it was announced the other day that military staff now have extra powers similar to that of a constable while managing a detention centre."

Billy Te Kahika Jr, NZ Public Party, August 29, 2020.

The Analysis

As military personnel play an increasing role in New Zealand's COVID-19 managed isolation and quarantine facilities, concerns are being raised that the Defence Force are being granted extra powers.

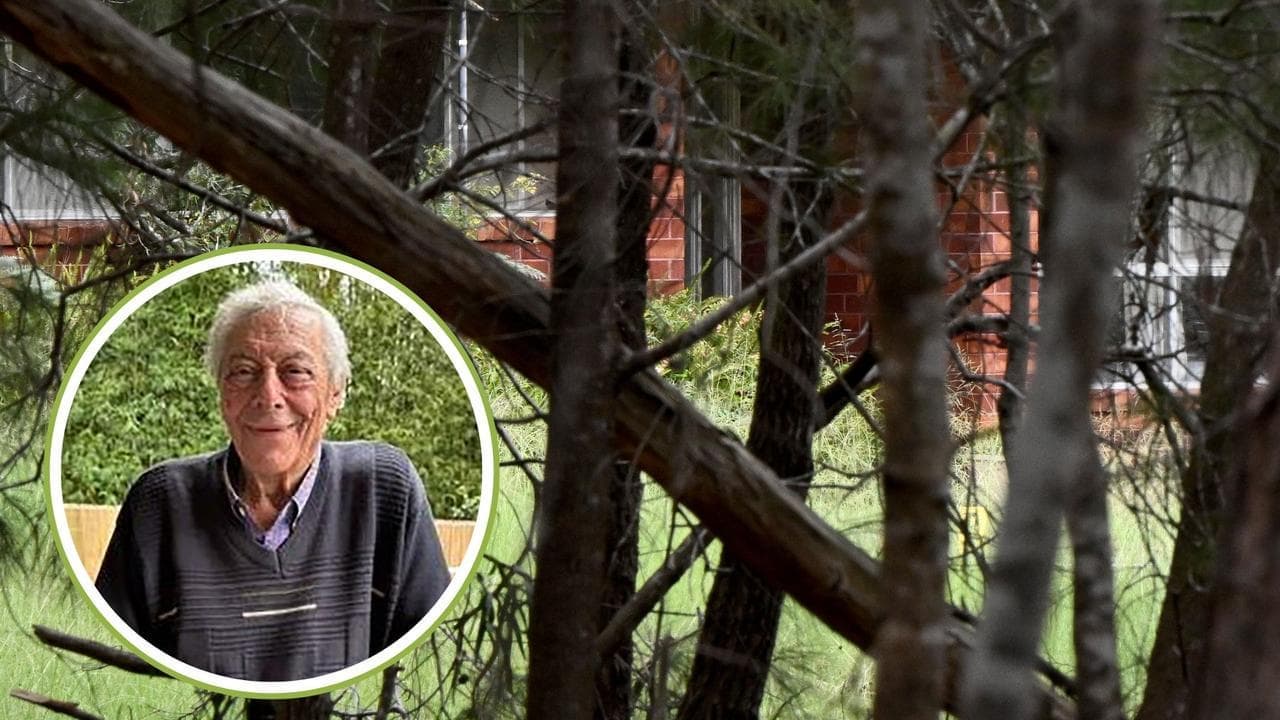

Around 1200 Defence Force personnel are now involved in the country's COVID-19 response, including about 990 stationed at managed isolation facilities. This has been criticised by Advance NZ co-leader Billy Te Kahika Jr, who has earlier made inaccurate statements that the Defence Force had been granted the power to enter private residences without a warrant.

During an interview on Newshub Nation on Three on August 29, Mr Te Kahika said the power of the military had been expanded and "we've got people's rights and freedoms being eroded". (Video mark 8min 32secs).

"So now, it was announced the other day that military staff now have extra powers similar to that of a constable while managing a detention centre," Mr Te Kahika said. (Video mark 8min 55secs)

AAP FactCheck examined Mr Te Kahika's statement that military staff have been granted powers similar to a police constable.

New Zealand's quarantine and managed isolation facilities have been partially staffed by the Defence Force since at least June 19, when numbers were doubled to 72. This was done after the government was criticised for allowing two people to leave managed isolation early, without being tested for COVID-19.

The role of the Defence Force has expanded significantly since, with Defence Force personnel increasingly taking over from private security guards in high risk facilities.

Members of the Armed Forces have also been stationed at vehicle checkpoints since August 12, supporting police at roadblocks in Auckland during the recent Level 3 lockdown.

Until recently Defence Force personnel reportedly had no more powers than a security. However, their powers were expanded on August 25, when Director-General of Health Dr Ashley Bloomfield authorised members of the Armed Forces to have the power to "give direction" and "to direct persons to provide identifying information".

These powers were granted by Dr Bloomfield under COVID-19 Public Health and Response Act 2020, which was passed on May 23 to enable the government to enforce measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Under Section 18 of the Act, the Director-General can authorise employees of the Crown to be an "enforcement officer" and grant them a range of powers, including to enter a property without a warrant.

However, on August 25, Dr Bloomfield only extended powers under Section 21 and Section 23 of the Act to members of the Armed Forces. This gives them the power to instruct a person not to break an order under the Act and the power to direct a person to provide identifying information, including their full name, full address, date of birth, occupation, and telephone number.

Not following these directions becomes an offence under the Act. These powers had earlier been granted to WorkSafe inspectors, Aviation Security officers and Customs officers.

So how does this compare with the powers of a police constable?

University of Otago law professor Andrew Geddis has written extensively on NZ's lockdown laws and told AAP FactCheck via email, that the powers granted to the Defence Force fall well short of those of a constable.

He said the key difference is that a constable has the power to arrest and detain people.

"Failing to comply with an enforcement officer's directions/requirement is an offence under the legislation - people 'have' to do what they say, or else risk prosecution," Prof Geddis said.

"But, and this is a pretty key difference, the military have no power to directly force people to comply with their directions/requirements.

"They have no legal power to arrest or detain, no right to physically restrain, etc. Only constables may do so (under their general policing powers)."

Prof Geddis explained that while a member of the military can stand at the entrance of a managed isolation facility and ask people to identify themselves, they can't enforce these directions.

"If a person ignores them, they can't grab them and hold them. Instead, they have to call in the police to effect an arrest," he told AAP FactCheck.

"As the defining feature of the police is the power to arrest and detain, saying that members of the military now have "similar" powers is false."

The Verdict

AAP FactCheck found the military have not been given powers similar to that of a police constable.

While the powers of Defence Force personnel working at quarantine and managed isolation facilities have been expanded, there are still crucial differences between the powers of a police constable.

While members of the Defence Force can legally require people to give basic personal information and order them to obey COVID-19 laws, they cannot enforce these orders like a police constable can.

False - The checkable claim is false.

* AAP FactCheck is accredited by the Poynter Institute's International Fact-Checking Network, which promotes best practice through a stringent and transparent Code of Principles. https://aap.com.au/